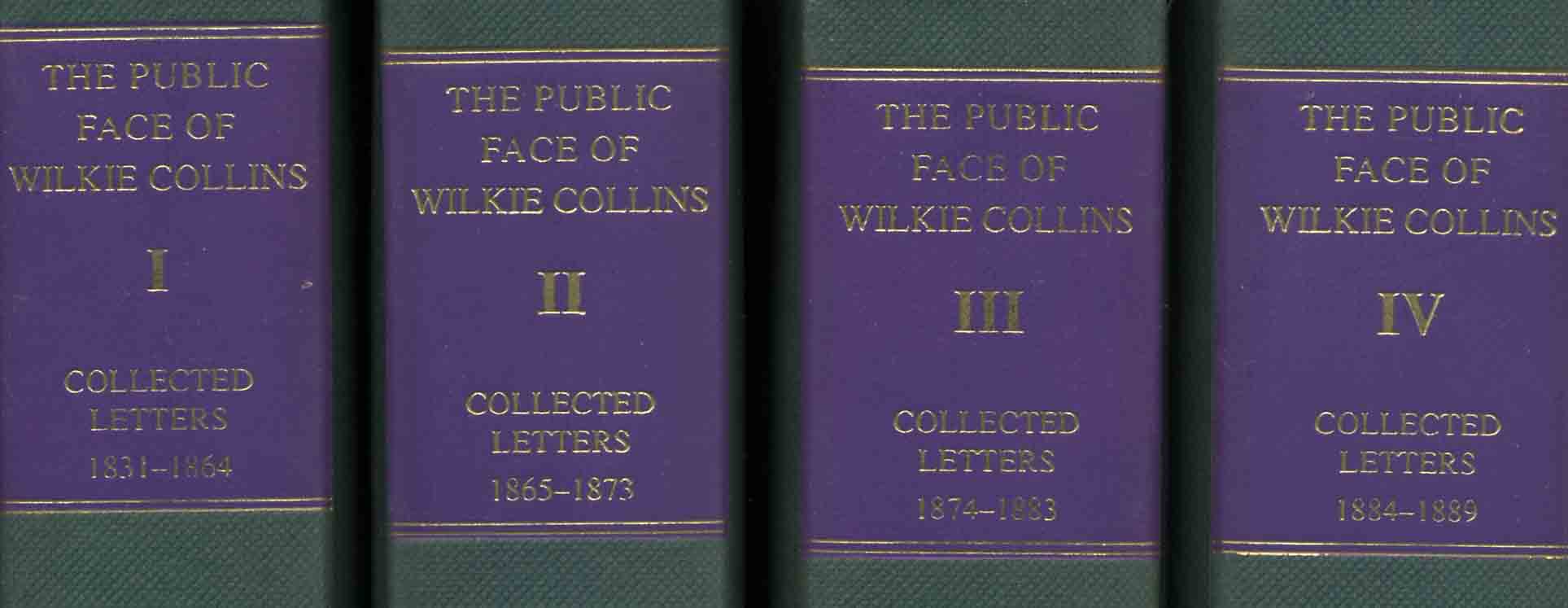

The Public Face of Wilkie Collins: The Collected Letters

Edited by William Baker, Andrew Gasson, Graham Law, Paul Lewis; Pickering & Chatto (ISBN 1-85196-764-8)

Summer 2005 saw the publication in four volumes of The Public Face of Wilkie Collins: the Collected Letters (Pickering & Chatto, ISBN-10: 1851967648) The four editors are Professor Graham Law (Waseda University, Japan), author of Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press; Professor William Baker (North Illinois University) who recently published Wilkie Collins's Library: A Reconstruction; Andrew Gasson, author of Wilkie Collins: an Illustrated Guide: and Paul Lewis who has also published extensively on Collins with a particular emphasis on his relationship with Dickens.

The current edition has identified almost 3,000 items of correspondence. Perhaps predictably, the majority of letters (1,854) are in the USA with the largest holdings at Princeton (697), Pierpont Morgan (275), Texas (270), Huntingdon (134) and Berg (129). The UK by comparison has about half this number (933) with significant holdings at Pembroke (328) and Glasgow (140); by comparison, the Bodleian and British Library have respectively just fifteen and thirteen. The remainder are scattered round the country in various and frequently obscure archives and museums. Letters have in addition been traced from as far afield as Germany, France, Poland, Japan and Australia. Apart from libraries, about 250 items held in private hands have also been traced.

An earlier, carefully selected edition, published by Macmillan in 1999, featured just 450 letters in full and about 120 in summary or partial transcription. With the current edition, all 3,000 letters are presented in strictly chronological order with approximately 2,500 transcribed in full and some 2,100 for the first time. For those previously included in the Macmillan selection, brief summaries and page references are given.

During the search for letters extraordinary discoveries have been made. Some were housed in an old carrier bag, one existed only as an offset mirror image and another was all but illegible through water damage. Reunited in this edition are letters with their lost envelopes and the beginnings of letters with their endings housed in different collections thousands of miles apart. One letter has been identified as a fake, an invention by the publisher Gardener Fuller endeavouring to 'authenticate' its 1862 piracy of No Name.

![]()

Collins lived an

unconventional, Bohemian lifestyle, loved good food and wine to excess, wore

flamboyant clothes, travelled abroad frequently, formed long-term relationships

with two women but married neither, and took vast quantities of opium over many

years to relieve the symptoms of ill health. Collins's circle of friends

included many pre-eminent figures of the day.

He knew the major

writers (Braddon, Elliot, Reade, Trollope) and more particularly Charles Dickens

with whom he regularly collaborated over many years.

In addition to a host of other novelists (Walter Besant, Hall Caine,

James Payn, George Augustus Sala, Edmund Yates), his circle of friends,

acquaintances and relatives included some of the foremost artists (Margaret

Carpenter, William Frith, Clarkson Stanfield, Edward and Sir Leslie Ward, Thomas

Woolner); playwrights (Dion Boucicault, Francois Regnier, George Rowe);

theatrical personalities (Mary Anderson, Frank Archer, Mary and Squire Bancroft,

Charles Fechter, Henry Irving, Wybert Reeve); musicians (Brinley Richards,

Franceso Berger, Nina Lehmann); publishers (George and Richard Bentley, Andrew

Chatto, Sampson Low, George Smith); physicians (Frank Beard, George Critchett,

John Elliotson); photographers (John Elliot, Napoleon Sarony, John and Herbert

Watkins); and society figures of the time (Lady Goldsmid, Gertrude Jekyll,

Lillie Langtry, Richard Monckton Milnes, Sir Henry Thompson and various Lord and

Lady Mayoresses)

All of these and

many others are represented directly or indirectly in Collins's letters.

They span the period from October 1831, with the seven-year-old

Wilkie writing to his mother ("My dear Mamma"), to September 1889 with the

dying novelist imploring his lifelong friend and doctor, Frank Beard, "I am dying

old friend ... Come for God's sake".

Missing from the letters, however, is any personal correspondence to the two women in his life, Caroline Graves and Martha Rudd, or to Collins's three children. There are alas only three letters to Dickens who notably destroyed all personal letters in his famous bonfire at Gad's Hill in 1860 and there is nothing to his close pre-Raphaelite friends Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais prior to this same period.

Other lifelong friends are better served. There are 109 letters between 1847 and 1879 to Charles Ward, an employee of Coutts & Co., who married Wilkie's favourite cousin Jane Carpenter, travelled on the Continent with him in the 1840s, acted as his unofficial financial adviser and was frequently pestered for advice on details for plots. Between 1851 and 1887 there are 59 letters to Edward Pigott, a fellow student at Lincoln's Inn who later became Examiner of Plays. Pigott became Collins's first regular employer in the 1850s as owner of The Leader and a frequent sailing and travelling companion. Other major correspondents are Wilkie's close friends Nina and Frederick Lehmann, editor and journalist Charles Kent and the American diplomat John Bigelow and his wife.

Friends from Wilkie's later years are also well represented. There is the remarkable correspondence between Wilkie and the twelve-year-old Anne le Poer Wynne and her mother from June 1885 to February 1888. Later friends include Harry Quilter, Walter Besant, Hall Caine, Frank Archer and William Winter. Many others date from the time of Collins's reading tour of the USA and Canada during 1873-4. Thus we have correspondence with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Napoleon Sarony, William Seaver, Kate Field, Paul Hamilton Haynes, and Sebastian Schlesinger.

Collins's unorthodox lifestyle reveals a cynical disregard for the Victorian establishment together with a sense of humour and a profound understanding for many of the then prevailing social injustices. These views, already reflected in his books, are expressed with an extra dimension in over 50 years of correspondence. They demonstrate Collins's skill as a descriptive writer with vivid portrayals of his travels at home and abroad. Other letters show his support for causes such as the anti-vivisection movement of the time. But more significantly, the letters reveal some fairly constant themes both personal and business.

![]()

On a personal level

we see Collins battling with ill health for most of his adult life.

A huge number of letters describe his perpetual battle with what he

called 'rheumatic gout'. We

witness his taking vast quantities of opium in the form of laudanum "measured

by table spoonful" to control

the symptoms as well as all kinds of attempts to cure himself from "The

Mesmerism [which] has prevented me from keeping my appointment"

to being "stabbed every night ... with a sharp pointed syringe which injects

morphia". He tries the baths at

Aix La Chapelle as well as some at home "Have you ever tried Caplin's

Electro Chemical Baths? ... They did wonders for me".

In his later years he suffered from angina: "Threatenings of the torture in the chest have made themselves felt - and have sneaked away again, without requiring the terrific treatment of the "Amyl". We also see him as his own worst enemy, over-indulging in both food "My style is expensive. I look on meat simply as a material for sauces." and likewise with drink: "A man who lives by the work of his brains, lives under artificial conditions - and must have artificial help. Natural Champagne (Vin Brut) is my help. In my experience there is no tonic for the exhausted nervous system, so effectual and so harmless."

The letters show an almost invariable politeness in responding to continual requests for his autograph or latest photograph. He shows great tact in declining an opinion on a stranger's manuscript or where to publish. On the other hand, he goes out of his way to advise friends on how to improve their work and to introduce them to publishers at home and abroad.

We see the charitable Wilkie, frequently prevailed upon to add his name to various testimonial funds, and in one case donating two pounds towards the funeral expenses of a former theatrical agent even though he proved to be an "irreclaimable scoundrel".

![]()

The personal and social correspondence accounts for just under half of the extant letters. The larger proportion, however, is concerned with publishers, editors, magazine proprietors, agents, printers, illustrators, translators and all those concerned with the business of publishing. These might be termed Collins's public letters and hence the title, The Public Face of Wilkie Collins.

Between 1868 and 1876 there are 125 letters to the solicitor, William Tindell. Tindell deals with general matters of business as well as drawing up Collins's publishing contracts prior to the arrival of A. P. Watt, the first literary agent. Watt is the largest recipient of letters and altogether 292 letters have survived from Collins's first tentative approach in December 1881 ("I am desirous of consulting your experience") to his last letter in June 1889, thanking Watt for arranging that Walter Besant should finish Blind Love. During this period as well as their business relationship the two become firm friends. A similar rapport exists between Collins and Andrew Chatto where 112 letters have been located. These are generally in a less formal tone than the 61 letters to the firm of Chatto Windus which became Collins's main publisher from 1875. Before this time he frequently changed publishers, looking for the best financial arrangement and trying to safeguard his copyrights. There is correspondence with Smith, Elder, Sampson Low, Bentley's, William Tinsley, Harper & Brothers in New York, Hunter Rose in Canada and Baron Tauchnitz in Leipzig. Also well represented are numerous minor figures from the world of publishing.

Letters to publishers are usually firm, direct and businesslike. Collins knew his worth and was unwilling to sell himself cheaply. But he was invariably fair so that when George Bentley lost money over Poor Miss Finch because of the machinations of W. H. Smith's and Mudie's Library, Wilkie immediately offered to "return to you whatever sum may appear on the losing side of the account." He called Mudie "the damnable despot" and was adamant in the case of The New Magdalen: "Nothing will induce me to modify the title. His [Mudie's] proposal would be an impertinence if he was not an old fool." He was equally uncompromising with Cassell's when they attempted to interfere with his text for The Law and the Lady

Perhaps the most significant theme that emerges from the business letters is that of copyright. Throughout his writing career Collins was at the forefront of demands for reform both in England and abroad; in 1884 he became an enthusiastic founder member of the Society of Authors. Over decades, he waged a constant battle with literary pirates in the USA and the letters to Harper's and other publishers show how careful he was to provide them with advance copy and give precise instructions as to the day of publication. A minor victory was scored in Holland when he forced the Belinfante Brothers to pay him royalties. In England, Collins published what he called 'bogus' editions of The Guilty River and The Evil Genius.

The theatre equally exercised Collins's mind and in the case of The Evil Genius he created a stage version for a single performance to protect his dramatic copyright. Here the letters show how for the same reason he came to write the stage versions of Man and Wife and The New Magdalen simultaneously with the novels. Once again Collins was aware of the international implications, writing to Laura Seymour "I am in danger of losing my copyright if this piece is produced first in America."

![]()

The letters have been extensively annotated throughout and where possible the other side of the correspondence has been consulted. With the benefit of the entire sequence, various errors of dating found in other published sources have been corrected and several previously undated letters have been allocated their correct chronological position with reference to watermark, style of notepaper and Collins's valediction.

The editors are located in London, Japan and Chicago so that the preparation of the present edition, although taking several years, could not have been completed in the same time without the use of modern digital technology - email for communication; digital photography and scanning for recording and assessing manuscript material; the internet for the immediate availability of online research sources; spreadsheets for statistical analysis and management of nearly 3,000 entries; and of course word processing for dealing efficiently with the eventual text. Wherever possible transcriptions have been checked by at least two editors. Collins's handwriting is frequently challenging, his punctuation idiosyncratic and spelling sometimes archaic (for example using 'negociation', 'recal' and 'to-day'). The ability to send an image around the world for a second or third opinion on difficult words and phrases has proved invaluable in the pursuit of accuracy. In some cases digital enhancement has permitted the deciphering of an otherwise unreadable manuscript.

The editors have used digital photography extensively and are extremely grateful to the many enlightened libraries and archives which willingly permitted digital images. In the interests of preservation, these can be taken without the use of intense illumination and cause less potential damage to documents than photocopying or even prolonged handling during transcription.

In conclusion, the letters interest and amuse us. They make us sympathise with Collins's agonies of ill health and share his indignation as we identify with the causes that he supports so fervently. If the early letters to his mother and young friends are full of youthful exuberance, then the final letters leave a degree of sadness as the dying novelist fails to maintain a hold on life. They reinforce the lasting impression that reading these letters in sequence bestows the privilege of knowing a major literary figure of the nineteenth century through the medium of his correspondence.

[ Top of page ] [ Back to Recent Books ] [ Front Page ]